exterminator, but she said that it was all part of the lesson. Shadowboxes of desiccated grasshoppers, cicadas, and dragonflies lined the tables. Petri dishes full of preserved spiders, scorpions, millipedes, and beetles were placed in front of the students. At the front of the classroom, a large cage that looked like it should hold a small songbird instead housed an enormous banana spider.

“Her name is Nellie,” said Mrs. Gier, “after her scientific name, Nephila clavipes. And it is her lunch time.” Nellie was hungrily devouring a bumblebee that was neatly wrapped in a nearly invisible strand of silk.

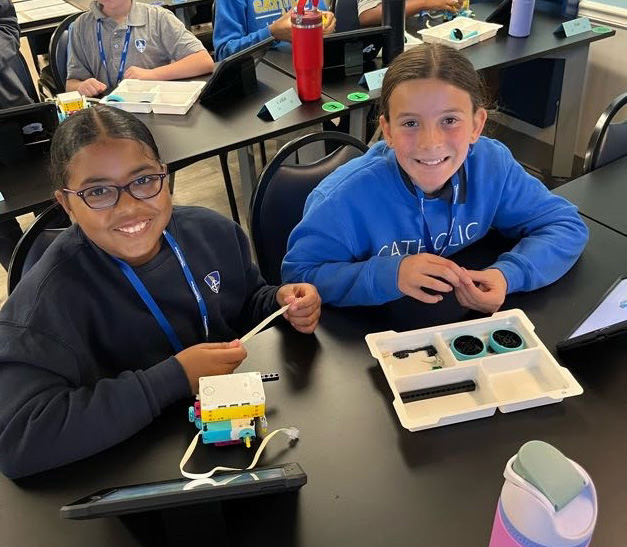

To some students’ delight and to others’ horror, their assignment was to open the dishes, delicately handle the specimens, and create a dichotomous key based on the physical traits of each arthropod. Each small group of students classified the various preserved insects, arachnids, and myriapods based on number of legs, presence or absence of wings, number of body segments, the shape of the mouth, and other traits. The students then used the keys they made to identify each specimen. While many students bravely picked up their specimens to get a closer look, others chose to take a supervisory role and instead took notes from a more comfortable distance. By the end of the period, each group was able to use the keys they created to identify the specimens that were classified by the other groups.

“Once students get beyond the ‘ick factor’, they discover that these small creatures, often overlooked, are fascinating and, dare I say it, beautiful,” said Mrs. Gier. “They are so important in our ecosystem and are the perfect specimens to instruct a lab on classification.”